As a public high school teacher and a parent I think often about the role of schools in our society and closely follow the current debate over school reform. Recently I read a concise, insightful letter to the New York Times that has stuck in my mind, almost haunted me, since —

To the Editor:

Standardized test scores can provide some evidence of what knowledge and skills students have learned. But lost in the debate is the fact that it’s possible to teach a subject well but to teach students to hate the subject in the process.

If one of the goals of schooling is to create lifelong learners, then high standardized test scores may be a Pyrrhic victory. That’s because long after the subject matter is forgotten, attitudes remain.

WALT GARDNER

Los Angeles, April 22, 2012

The letter reminds us that debates over school quality and the so-called reform movement have the power to distract from more fundamental questions about the role of education in our society. Schools that we might consider successful — producing a lot of university bound students with high test scores — may fail completely to cultivate the curiosity and engagement that create lifelong learners.

The author of the letter, Walt Gardner, maintains a blog at Education Week called Reality Check. His May 2 post continues the theme with a critique of a recent Wall Street Journal op/ed by former George H. W. Bush Secretary of State George Schultz and economist Erik Hanushek, a prominent proponent of “value-added” measures of teacher performance. Schultz and Hanushek, both fellows at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, argue that the sluggish growth of the U.S. economy would change dramatically if we embraced school reform. High science and math scores lead to increased economic output, they write.

Schultz and Hanushek are both are part of what has come to be known as the education reform movement. I don’t want to over-generalize the reform position, but it’s fair to say that they advocate using standardized testing as a key component for identifying schools that should be de-funded and teachers who should be fired, this would result in greater efficiencies at the school level. To the reformers, a move toward charter schools is positive because they are less constrained by local districts and teachers’ unions.

In his blog post, Gardner questions the causal relationship Schultz and Hanushek make between  test scores and economic growth, pointing out that Japan, high scoring yet mired in a slow economic growth since the 1990’s, doesn’t fit their model. He also raises the point that broader economic policies (e.g., spending cuts in a recession) and the realities of international competition cloud the test-score-to-economic-growth relationship even further.

test scores and economic growth, pointing out that Japan, high scoring yet mired in a slow economic growth since the 1990’s, doesn’t fit their model. He also raises the point that broader economic policies (e.g., spending cuts in a recession) and the realities of international competition cloud the test-score-to-economic-growth relationship even further.

Gardner’s criticisms are sound, but in the spirit of his letter to the Times, I’m inclined to point to a more fundamentally distressing aspect of this piece, and the reform movement in general.

Much of the proposed reforms are an attempt to squeeze more “value” out of teachers, as measured by tests that may work to some degree in areas like math and science, but resist easy standardization in almost everything else that is supposed to happen in a school – from history to literature to art, to even less measurable skills like critical thinking, maturity, and, as Gardner’s letter to the NY Times reminds us, hanging on to the curiosity and love of learning we all had as children.

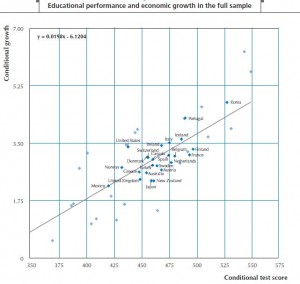

When the education economists associated with the reform movement look at a school they see teachers creating measurable “learning gains” in their students. For example, students of a bad teacher might only gain .5 years of learning in a calendar year, while the students of a good teacher gain as much as 1.5 years in the same time span. Hanushek’s emphasis is on the impact that this “value added” by a teacher will have on the lifetime earnings of students, and ultimately on the nation’s overall economic output. His policy proposal follows logically from there. He argues that by removing the worst 5 to 10 percent of teachers and replacing them with average teachers, the United States will, over time, achieve test scores as high as Finland’s (see graph). To be fair, Hanushek says the identity of the bottom 5-10 percent of teachers wouldn’t be based on test scores because the “obviousness … would be revealed by virtually any sensible evaluation system.” He identifies teachers’ unions as the biggest obstacle to such a plan.

The issue of unions is a distraction. Many of the worst performing states are right-to-work, where unions are either non-existent or weak. We strive for the test scores of Finland, a country where teachers are 100% unionized and the societal approach to education is radically different than in the United States. Hanushek’s proposal is like a doctor prescribing liposuction to an out of shape patient when what is obviously needed is a healthy diet and active lifestyle. Why is it that marginal, misguided proposals like these have such traction in the education debate?

The reforms advocated by economists like Hanushek are well received in a political atmosphere where public institutions, and the people who work in them, are viewed with suspicion. It is difficult to imagine a national dialogue about building a public system based on professionalism, trust, and responsibility in today’s political climate.

Just as a prolonged recession and soaring debt have placed long established social programs on the chopping block, in the hands of Hanushek and Schultz the economic crisis becomes an argument for their version of school reform. What would successful reform bring to our society? A 40 point increase in math scores for U.S. students over the next 20 years, they claim, would net “an increase in GDP over the next 80 years would exceed a present value of $70 trillion. That’s equivalent to an average 20% boost in income for every U.S. worker each year over his or her entire career.” This, to them, is what schools do.

And that brings me back to Walt Gardner’s wonderful, haunting letter. The economists of the reform movement tempt us into a debate that accepts the premise that schools are an place where teachers add value to students, boost their lifetime earnings, and in the aggregate raise the output of the national economy. It isn’t enough to disagree with liposuction as the prescription for a troubled school system. We need to be animated by a vision of what we want schools to be like in our society – a place to develop the habit of learning that will last a lifetime.

Rather than wring our hands over how to remove teachers who shouldn’t be teaching (a problem that is always made out to be more difficult than it actually is), we ought to approach schools as an institution, and teaching as a profession, in a different way. Schools ought to be rooted in, and accountable to, their own communities. Time in the school year should be provided for a teacher to deepen their knowledge of the field they teach, to collaborate with peers in order to share ideas and skills, and to meet the individualized needs of students. If we as a society understand that the majority of teachers enter the field because they want to be good at teaching, we ought to create institutions where they can thrive.